Mortality in the Kali Yuga

The persistence of death in the unfolding of cosmic manifestation.

Emerging from the optimism of the 1990s, out of the age of the war on terror, it seems evident that in the broader zeitgeist, dreams of utopic scientific world peace have run their course, and in their wake arose an ideation of decline, disorder, and prophecies of doom. Among the political left, whole governments have adopted “green solutions” to slow or even reverse the changes to our globe’s climate, and on the political right themes of cyclical decline have entered the intellectual discourse with the rediscovery of thinkers like Rene Guenon and Oswald Spengler. This reaction is not unwarranted, there is truth to this pessimism observable in the signs of our times, but that is not the concern of this article.

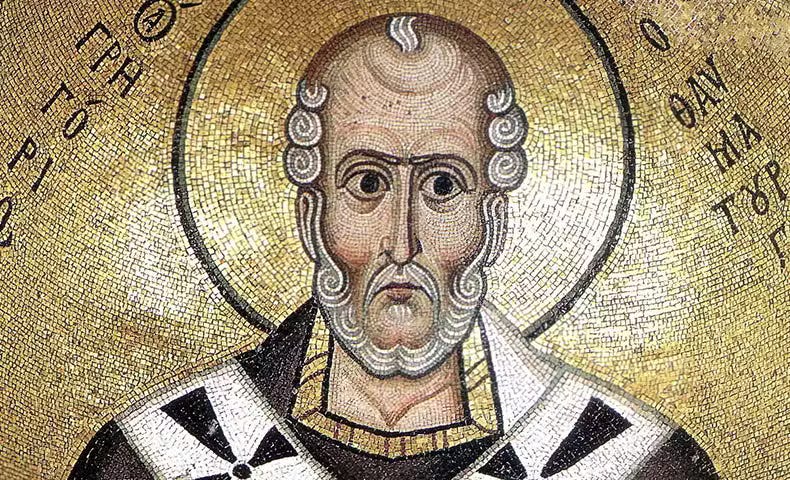

This preoccupation with death is at the root of the whole civilisational enterprise. Schooling to cultivate wisdom, policing to prevent crime and maintain public order, hospitals to heal the sick. All of these exist precisely to avoid death. As Saint Gregory Nyssa says in his dialogue, On the Soul and the Resurrection:

“We see before us the whole course of human life aiming at this one thing, viz. how we may continue in this life; indeed it is for this that houses have been invented by us to live in; in order that our bodies may not be prostrated in their environment by cold or heat.”

Mankind developed civilisation out of necessity to cope with this reality, encompassing not merely the labour of civilisation, but likewise its cultural awareness. In his magnum opus, the Decline of the West, Oswald Spengler outlines a universal pattern of the rise and fall of civilisations. He identifies that a fascination with death marks both the birth of a civilisation and the birth of its religious feeling. Burial practices, sacrificial offerings, and apocalyptic imagery are signs of this cultural awakening. As Spengler so beautifully puts it, with an awareness of death comes an understanding of transience and being:

“Only fully-awakened man, man proper, whose understanding has been emancipated by the habit of language from dependence on sight, comes to possess (besides sensibility) the notion of transience, that is, a memory of the past as past and an experiential conviction of irrevocability. We are Time”

Spengler’s analysis of man’s fascination with death, however, stays within the confines of historical inquiry. In the writings of the metaphysician, Rene Guenon, we find a more universal study of decline that comes to encompass the whole of providence. Where Spengler studies culture from a distance as a historian, Guenon approaches it with the same metaphysical lens through which these cultures pictured the world. To Guenon, culture was no mere creation of man’s outlook, but an expression of universal and eternal principles. Of keen interest to him was the Yuga cycle of Vedic cosmology, an idea that the very unfolding of time itself occurred cyclically, repeating in the same pattern as it previously did. This was a cycle of four progressively degenerating ages; each further removed from the primordial principle of divine perfection than the last.

Parallel to this fall of ages is a descent into increasing materiality and multiplicity. As Guenon says in his The Crisis of the Modern World, “any manifestation necessarily implies a gradually increasing distance from the principle from which it proceeds.” In accordance with Aristotelian metaphysics, an effect can be no greater than its cause, and with the first cause being infinite and its effects being finite, these latter causes cannot bring out, from their own being, more than what they are, by virtue of their limited nature. Moreover, there is a downward tendency as the level of differentiation that increases in the chain of causality leads to further fragmentation, each effect more limited than its cause. The chain of causal manifestation thus necessitates that from oneness rises multiplicity, or as Guenon describes it, “progressive materialisation.”

The ages of the Yuga cycle are also reflected in the ages of man recounted by Hesiod, one of the earliest ancient Greek poets: the golden, silver, bronze, heroic, and iron ages. He writes in his Works and Days that at the beginning men lived like gods, “remote and free from toil and grief”, and that “dwelt in ease and peace upon their lands with many good things, rich in flocks and loved by the blessed gods.” Man in this age lived life abundantly without hardship, in harmony with the natural order of the gods. But succeeding this in the silver age, he describes that man was less noble, sinning and wronging one another, and living only a short time, with these symptoms of finitude and sin increasing with each progressive age. Sin and death were understood to be parallel and inseparable over the course of providence.

The final age of iron, according to Hesiod, was the one in which he and us find ourselves in, where men dishonour their parents, oaths are no longer kept, and evildoers are praised. “Envy, foul-mouthed, delighting in evil, with scowling face, will go along with wretched men one and all,” he judges. This last age is reflected in the Yuga cycle by the Kali Yuga, Kali translating to vice, discord, confusion, or strife. It is also the name of the demon who possesses Duryodhana, the chief antagonist of the epic Mahabharata, embodying the malevolent forces previously outlined and presiding over the Kali Yuga.

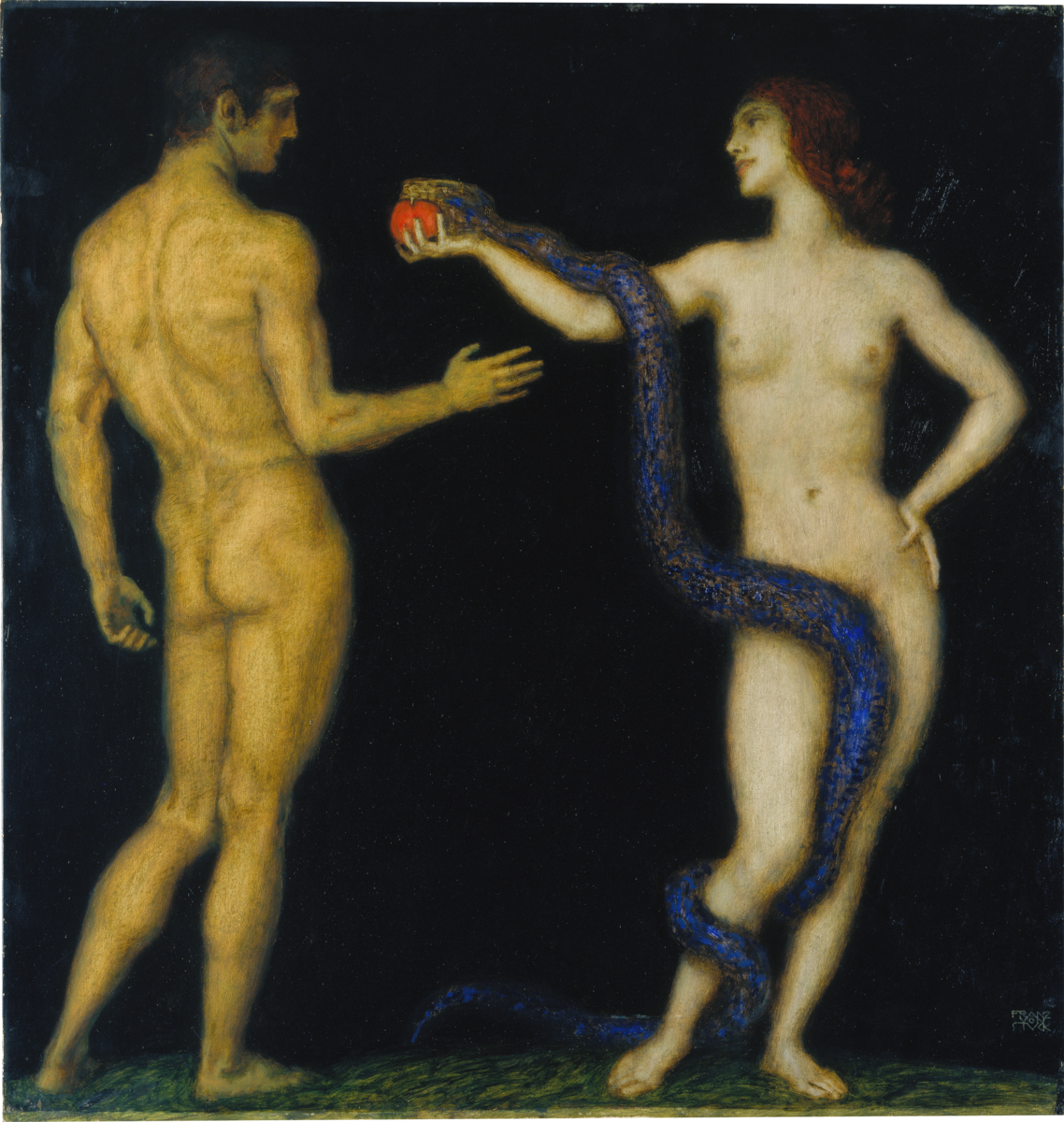

The Genesis narrative of the Jewish and Christian traditions also identifies this connection between sin and death, but more clearly emphasises their causal relationship in the initiating event of the fall. That by eating of the tree of which God told they would surely die, in Adam and Eve’s transgression, death came into the world, “for dust you are and to dust you will return” (Genesis 3:19). Thus, was the fall of man, and so too, the fall of all creation. As scripture says, “cursed is the earth because of you” (Genesis 3:17). With that first transgression collapsed an entire reality; the collapse of the cosmic order from the perfection of the earthly paradise into the fragmented, impermanent world of man’s continuous sin and fall. Although Adam would live a total of 930 years after the fall, his descendants would live progressively shorter lifespans. Seth lived 912 years; Enosh, 905 years, until we find ourselves now living hardly passed a hundred.

Throughout the whole array of civilisations, this idea of a fallen and transient world recurs as an intuition. Death is utterly inevitable. It is an empirically obvious truth. The laws of physics demand all things move toward dissolution. Entropy increases; energy degrades and dissipates. Organisms, stars, and galaxies break down when the energy sustaining them runs dry, with the whole universe eventually reaching a point of thermodynamic equilibrium.

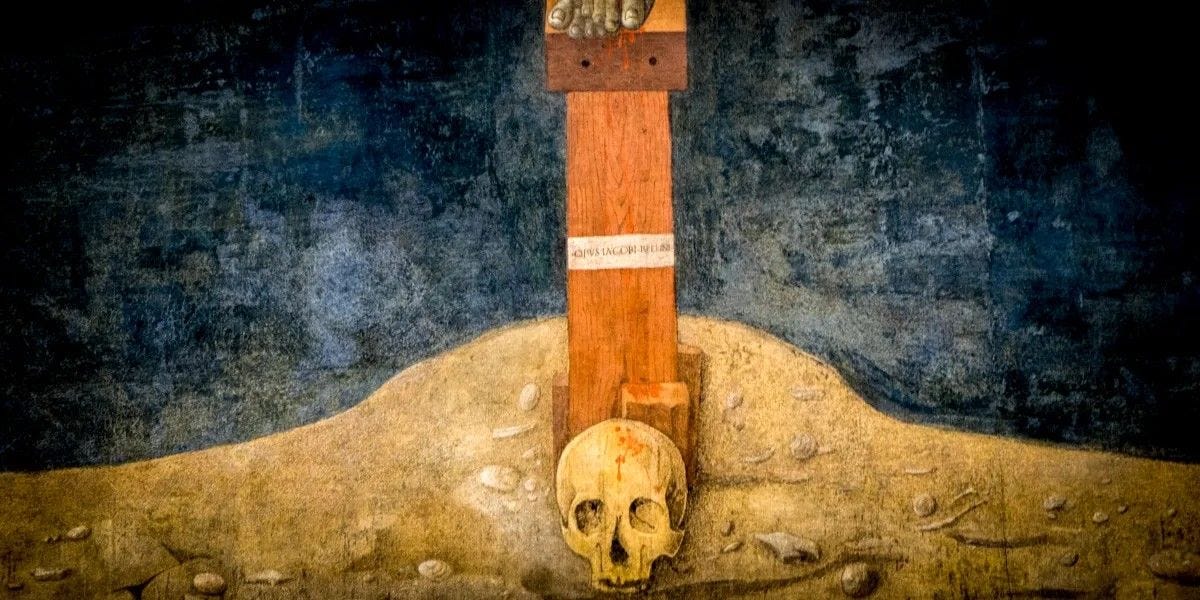

But if what Biblical tradition tells us is true, that this disorder and tendency to decay in the natural world corresponds on the macrocosm to the faultiness and deformity of humanity, not just in the body but in the soul as sin, then likewise as the Bible teaches, might the healing of the soul entail the restoration of the world? As Saint Paul tells us, “The whole creation has been groaning as in the pains of childbirth right up to the present time” (Romans 8:22). We await together in hope as God’s creation. But how does the salvation of one lead to that of the other? We are promised a new Eden, but what is this tangibly? Some mode of association must be identified. Spirit and matter must be reconciled in some respect. On this question rests the whole framing of Christ’s resurrection and mankind’s destiny. Much of human history following Christ’s death has been in the struggle to answer this, each answer having vastly different civilisational consequences, often disastrous in nature. But as profound a question that may be, we can be sure from this that the tree of knowledge and original sin persist in mankind, encompassing the whole course of providence and the moral struggle enduring within it.

Nevertheless, beyond death, and in defiance of it, there is the glorification of life. The Roman cult of Fortuna and the cornucopia as a symbol of abundance, Saint Thomas Aquinas’ affirmation of the good pleasures in the moral order (see his Summa Theologiae, I–II, q.34), and the whole history of poetry, visual arts, and entertainment are a testament to mankind’s celebration of life. Both myth and secular narrative oscillate between victory and defeat. Christ’s passion, his resurrection, and his promise of eternal life, affirm simultaneously the inevitability of death and its overcoming. But what attitude, what ethos, leads to which destiny as the fate of the world oscillates? Civilisation has already hinted. Therefore, an investigation into the destiny of men of previous epochs is necessary, and the ultimate purpose foreseen in their thought.